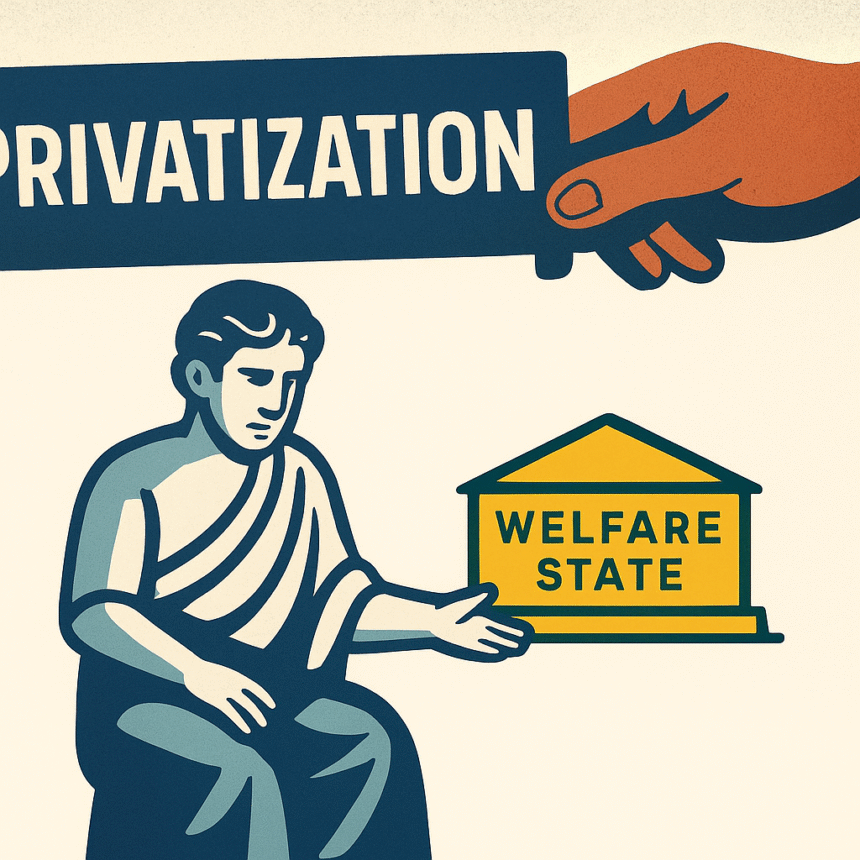

Pakistan is a welfare state. Usually welfare states in the world tried to establish the welfare institutions to serve the weak and poor part of population. Unfortunately pace at which Pakistan’s government is pursuing privatization has crossed the threshold from economic restructuring to a potential national identity crisis. This is no longer merely an exercise in shedding loss-making entities; it is an aggressive push into strategic and social sectors that form the very backbone of the republic. From the iconic, yet troubled, Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) and the dormant Pakistan Steel Mills to the profoundly essential domains of education and healthcare, the state is seemingly embarking on a massive liquidation of its own assets. This process raises a chilling question: What is the true cost of this sell-off, and what will remain of the government’s authority once all its major assets are in private hands?

The primary argument peddled by proponents of privatization is efficiency. They argue that private sector management, unburdened by bureaucratic red tape and political interference, can turn around perennial losers like PIA or make the Steel Mills profitable. While this may hold true in a strictly commercial sense, it dangerously overlooks the core nature of these ‘Quami Asaasajat’ (national assets).

These assets were not established solely for profit; they were created to serve strategic and social objectives. PIA, for instance, is not just an airline; it is a strategic asset for national connectivity, emergency response, and upholding the Pakistani flag across the globe. The Steel Mills, despite their operational struggles, were meant to be the ‘commanding heights’ of our heavy industry, a source of local employment, and a crucial pillar of self-reliance.

When a public hospital or a government school is handed over to a private corporation, the concept of social justice is the first casualty. A public institution is compelled, by its very nature, to treat all citizens equally, regardless of their financial standing. A private entity, driven by its shareholders, will invariably priorities revenue. This means the costs will rise, and access to quality healthcare and education—fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution—will become a privilege reserved for the affluent. This hollows out the state’s moral authority and exacerbates inequality.

The most alarming aspect of this rapid divestment is the consequential erosion of the government’s ‘writ’. A sovereign state is defined not just by its borders but by its ability to control the levers of its economy and social infrastructure. When the government sells off its key institutions, it effectively surrenders its ability to intervene in times of crisis, regulate prices effectively, and ensure universal access.

Consider a scenario where all major hospitals are privatized. If a national health crisis or pandemic strikes, the government will be in a weak negotiating position, forced to plead with private owners—whose primary motivation remains profit—to comply with national interest. The government, in essence, becomes a mere feeble regulator of powerful private monopolies rather than the guarantor of its citizens’ well-being.

The sale of these assets represents the loss of powerful market intervention tools. A public sector entity, even at a loss, can be used to set a benchmark for pricing (like utility companies) or to maintain employment levels during economic downturns. Once these levers are gone, the state loses its capacity to actively shape the economy for the benefit of the common man. The ultimate responsibility for public welfare remains with the government, but the tools to execute that responsibility are systematically dismantled.

While the immediate financial relief from a mega-sale looks tempting on paper—helping to plug budget deficits or retire foreign debt—it is a fiscally short-sighted solution. It is akin to selling the family jewelry to pay for the monthly grocery bill. The revenue generated is a one-time injection, but the national asset that had the potential to generate long-term value, employment, and strategic influence is permanently gone.

Furthermore, the process is often conducted under opacity, raising serious concerns about asset valuation and potential favoritism. Are we truly getting the fair market price for decades of public investment, or are these national treasures being offloaded in a hurry, only to be snapped up by a few well-connected entities? The lack of transparency fundamentally undermines public trust in the entire process.

Privatization is not an absolute evil, but it must be an act of strategic reform, not desperate liquidation. The focus should be on making public sector entities efficient under public ownership, through robust governance, professional management, and freedom from political interference. Where privatization is unavoidable, it must be executed with extreme caution, maintaining state control over core strategic assets and ensuring the social sector (healthcare and education) remains firmly under the umbrella of public provision or under strictly monitored public-private partnerships that prioritize access and affordability over profit.

The current trajectory risks reducing the Pakistani state to a minimal, revenue-collecting entity devoid of control over its own critical infrastructure and social future. We must pause, reflect, and ask ourselves: Are we truly ready to trade our national control and social promise for a temporary financial fix? The cost of losing the soul and the essential writ of the state will be far higher than any financial benefit reaped today.